|

Text: James D Campbell, 2014

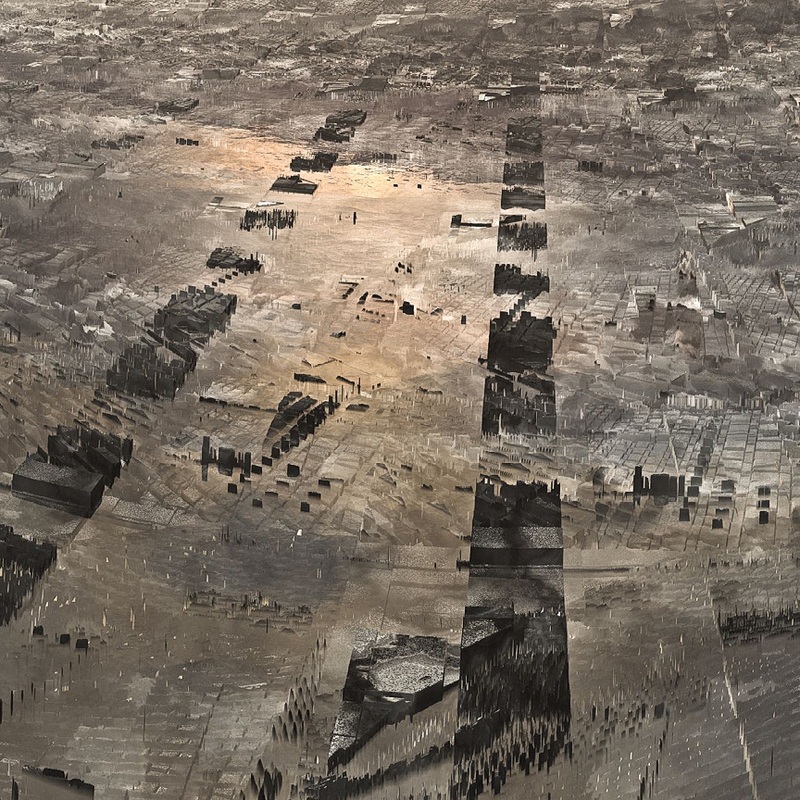

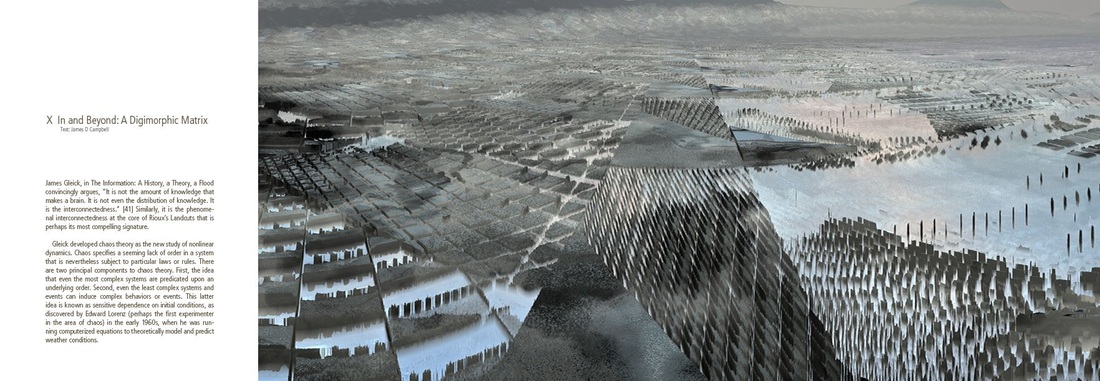

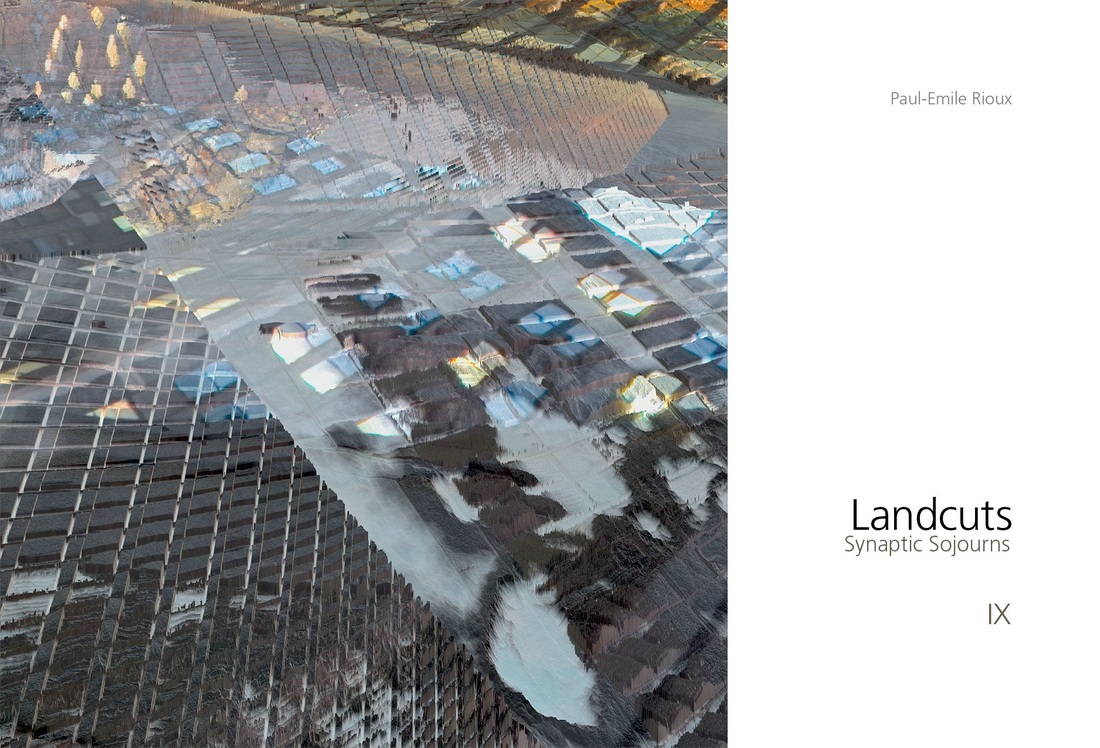

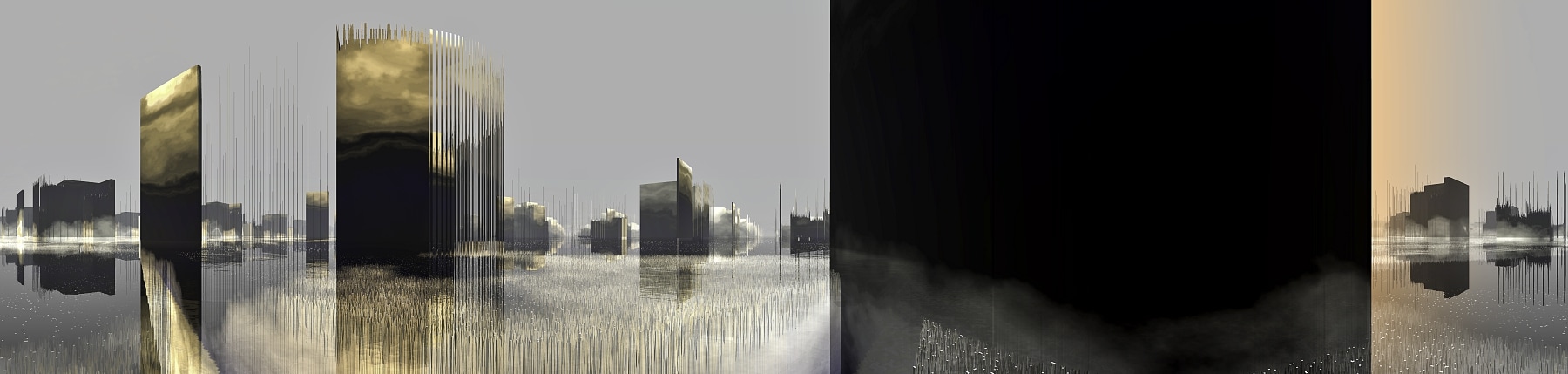

James Gleick, in The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood convincingly argues, “It is not the amount of knowledge that makes a brain. It is not even the distribution of knowledge. It is the interconnectedness.” [41] Similarly, it is the phenomenal interconnectedness at the core of Rioux’s Landcuts that is perhaps its most compelling signature.

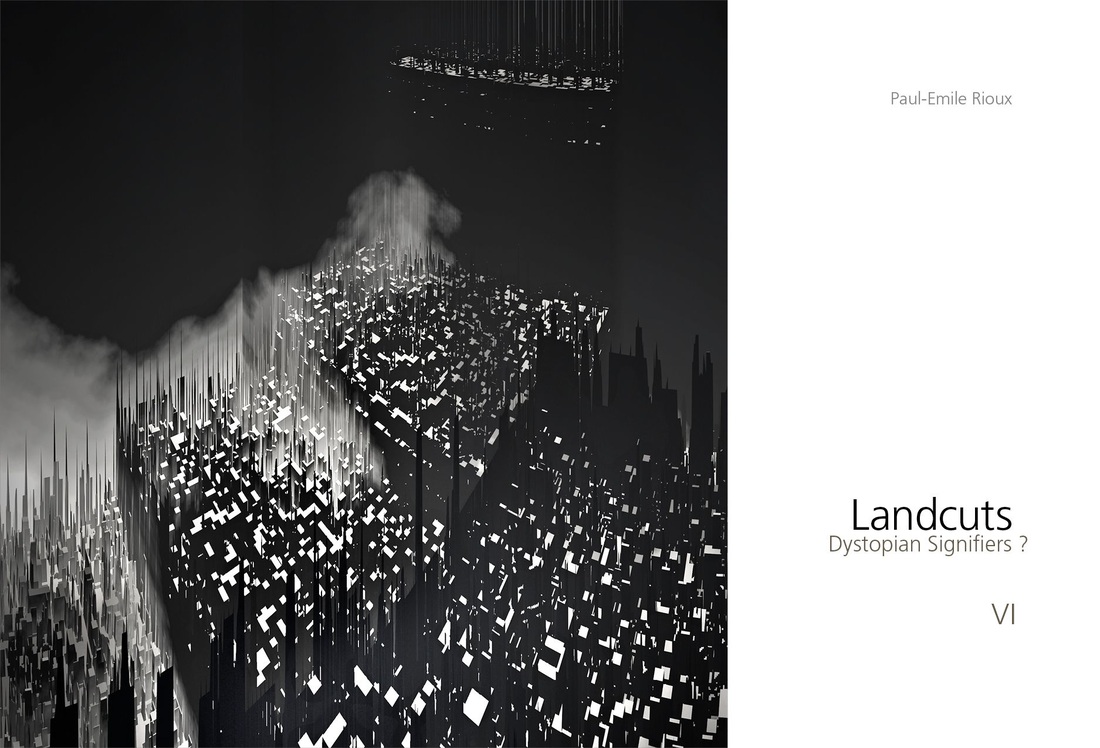

Gleick developed chaos theory as the new study of nonlinear dynamics. Chaos specifies a seeming lack of order in a system that is nevertheless subject to particular laws or rules. There are two principal components to chaos theory. First, the idea that even the most complex systems are predicated upon an underlying order. Second, even the least complex systems and events can induce complex behaviors or events. This latter idea is known as sensitive dependence on initial conditions, as discovered by Edward Lorenz (perhaps the first experimenter in the area of chaos) in the early 1960s, when he was running computerized equations to theoretically model and predict weather conditions. He ran a specific sequence, replicated it and expected the same results. But they were quantitatively different. He concluded that even the most infinitesimally small variation in preliminary conditions effectively made prediction of past or future outcomes impossible. [42] Lorenz’s description of the so-called “butterfly effect” seems a lovely and fitting default template for Rioux’s Landcuts. At the December 1972 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., Lorenz captured the living essence of chaos theory in his “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly's Wings in Brazil Set off a Tornado in Texas?”. The example of such a small system as a butterfly being responsible for creating such a large and distant system as a tornado in Texas illustrates the impossibility of making predictions for complex systems; despite the fact that these are determined by underlying conditions, precisely what those conditions are can never be sufficiently articulated to allow long-range predictions. [43]

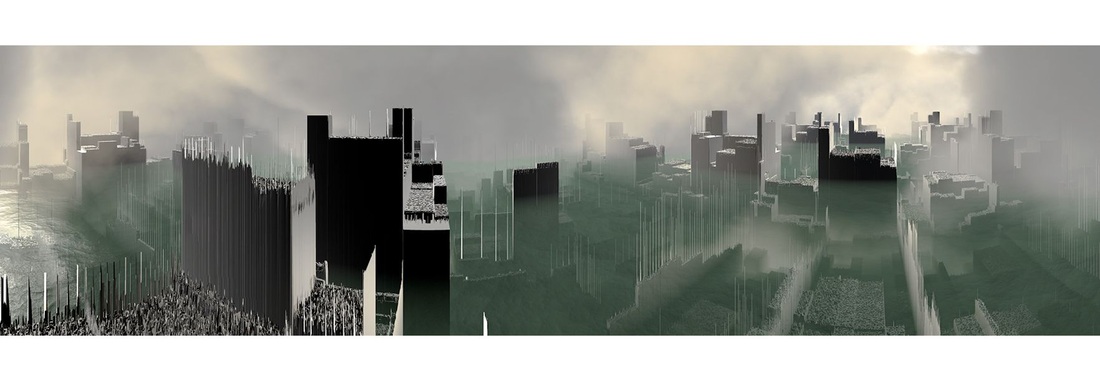

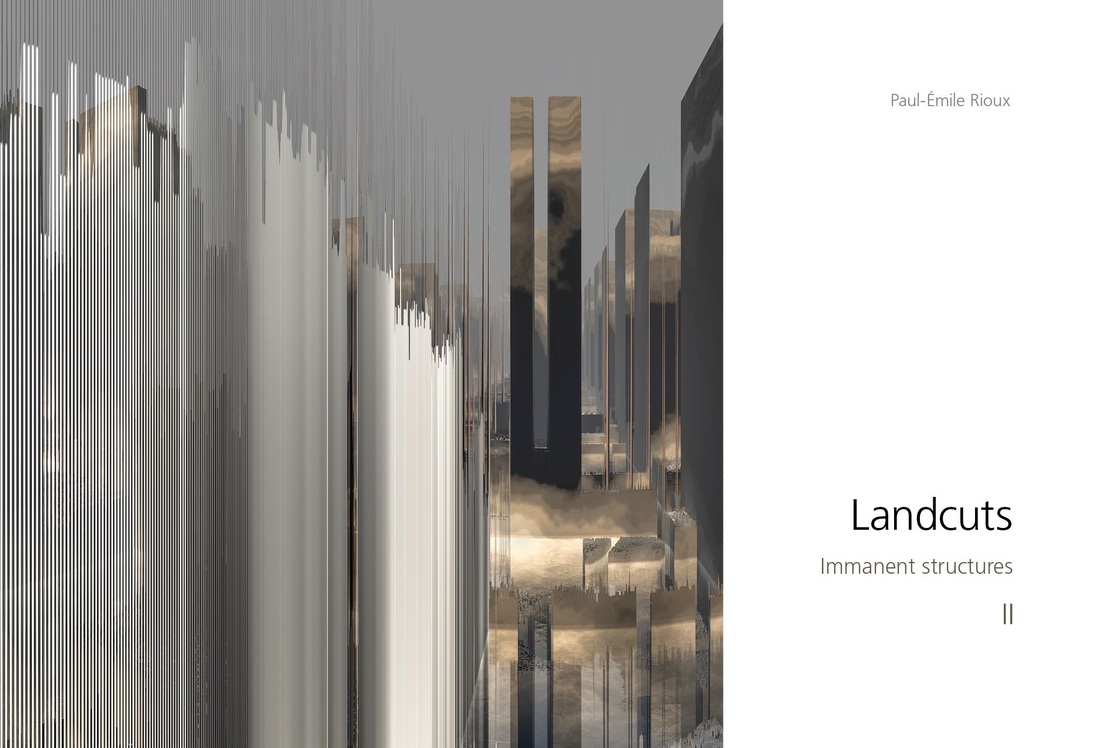

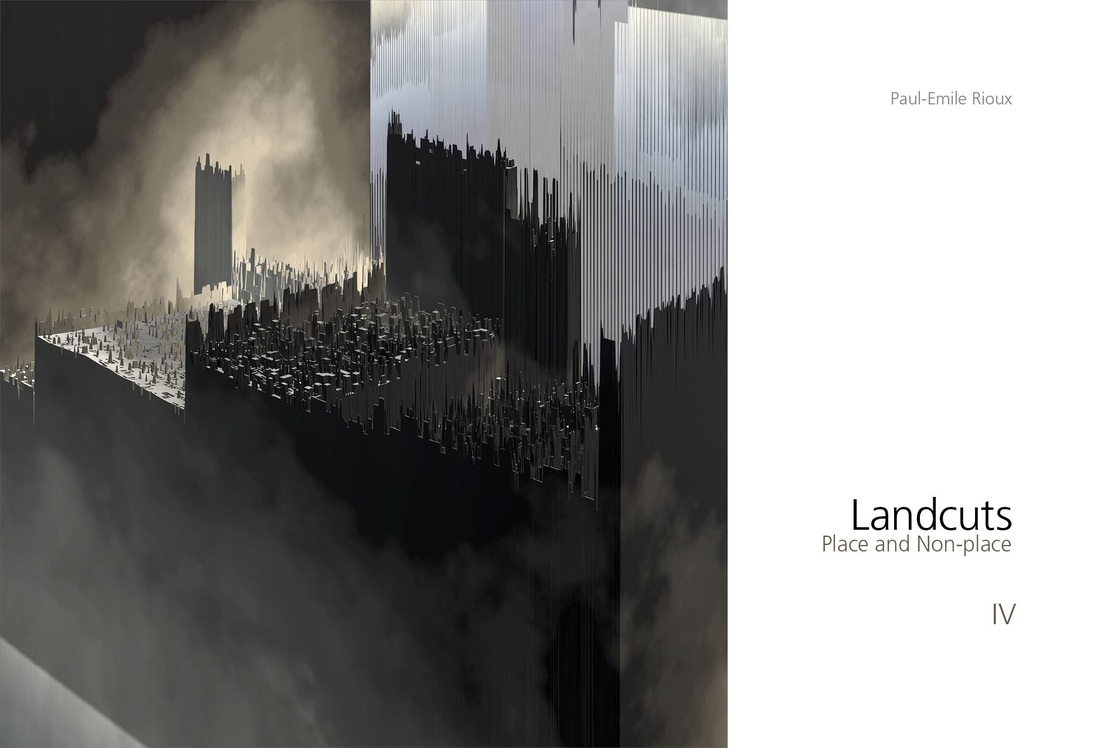

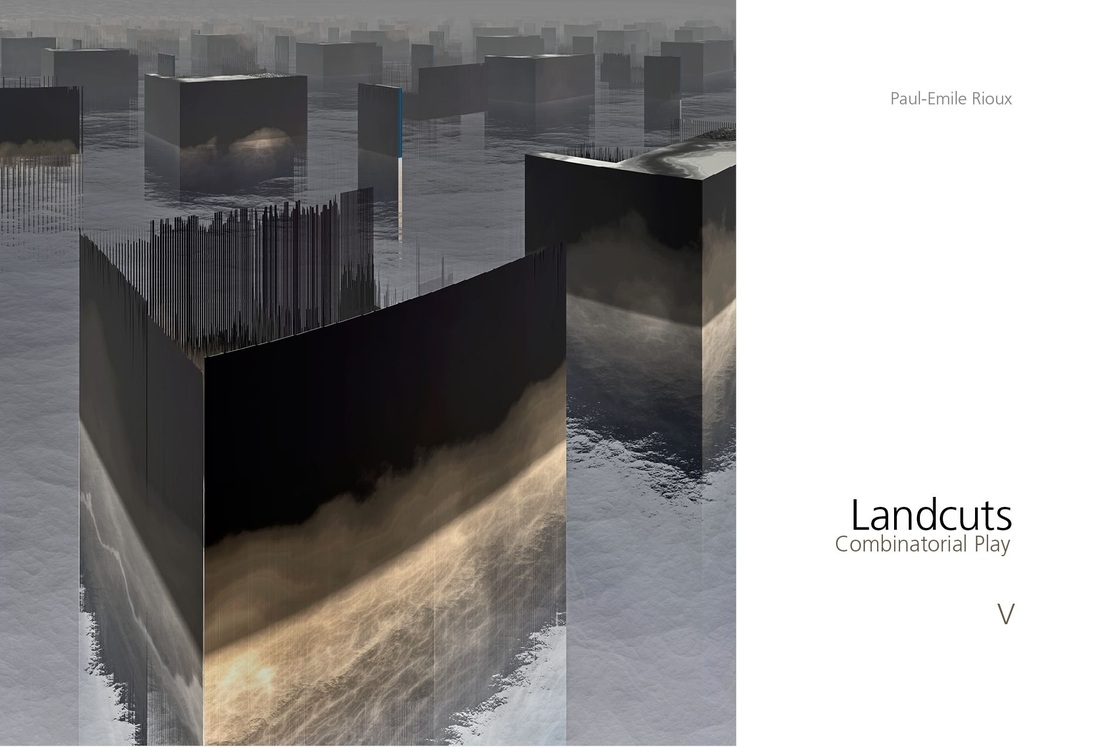

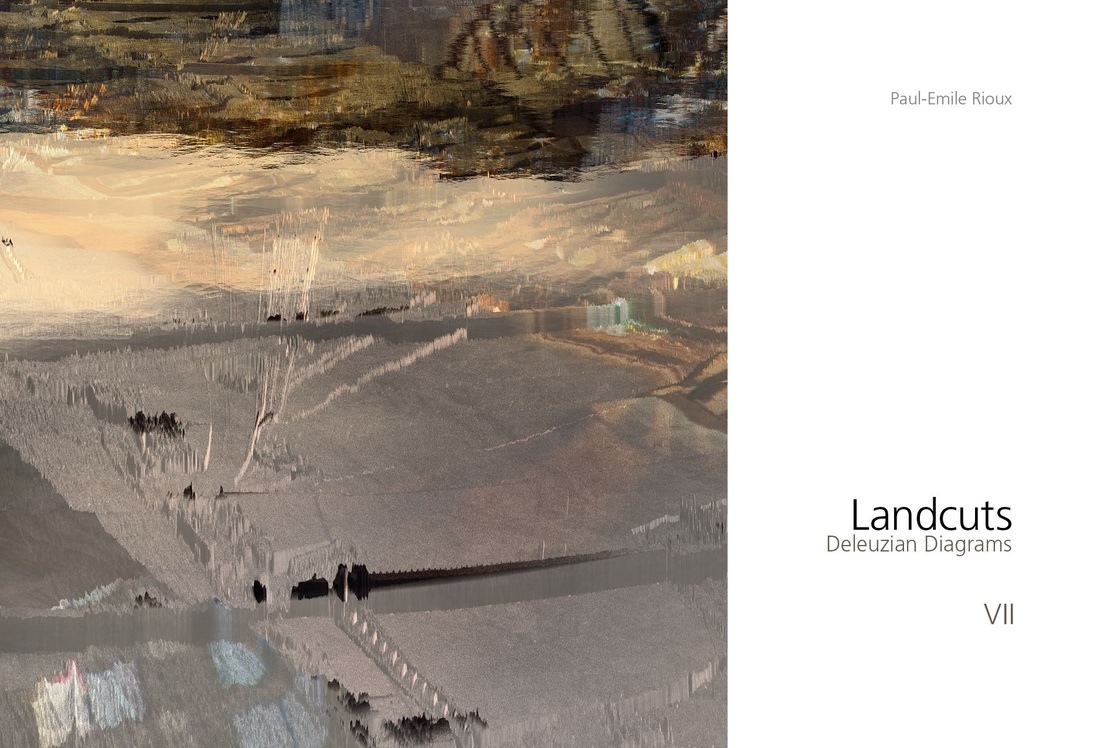

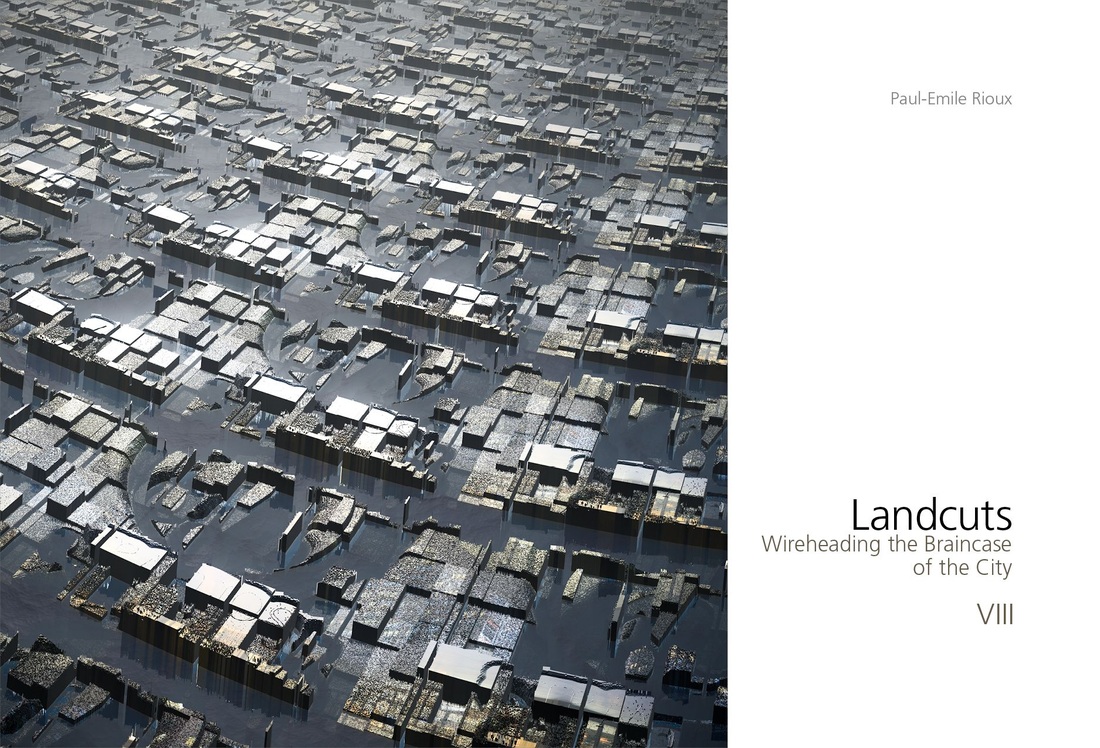

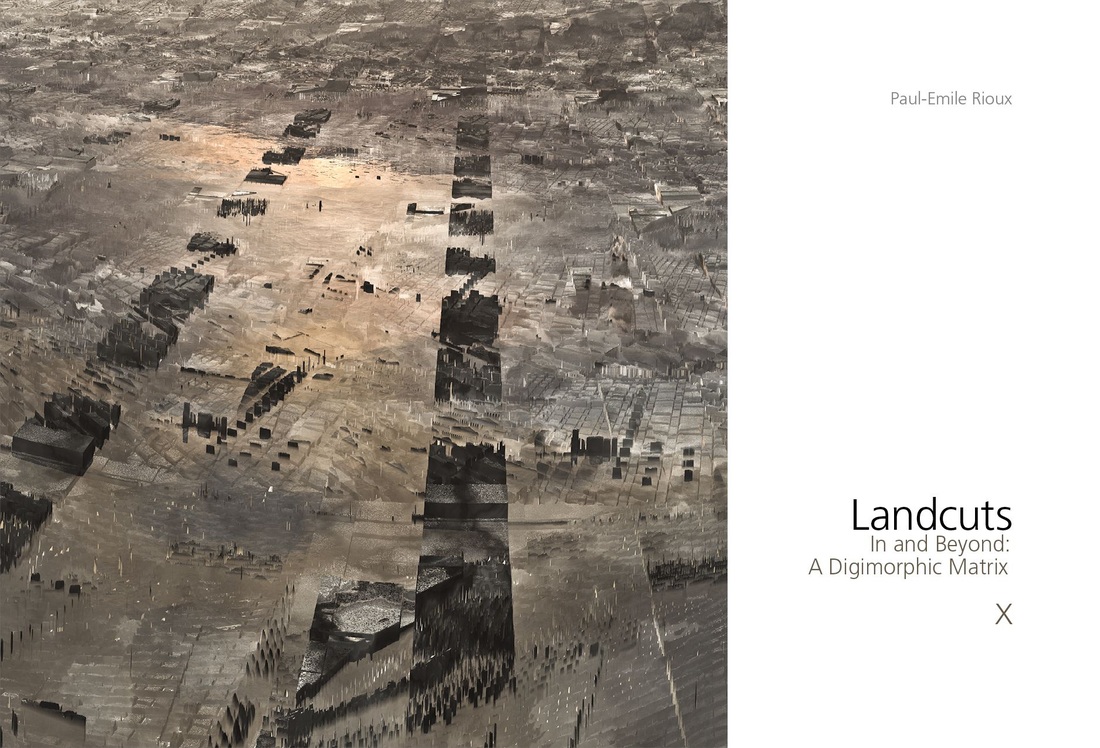

Although chaos is often construed in terms of randomness and lack of order, it is in fact far more judicious to think of it as an apparent randomness that results from complex systems and interactions among those systems. According to Gleick, chaos theory is “a revolution not of technology, like the laser revolution or the computer revolution, but a revolution of ideas. This revolution began with a set of ideas having to do with disorder in nature: from turbulence in fluids, to the erratic flows of epidemics, to the arrhythmic writhing of a human heart in the moments before death. It has continued with an even broader set of ideas that might be better classified under the rubric of complexity.” [44] Now, this dovetails beautifully with Rioux’s Landcuts, wherein the “machinic” (in the Deleuzian sense of exceeding both organic and technical) suggests highly evolved, unprecedented, interconnected and self-replicating communities of collective and complex subjectivities disguised as architecture. The richly organized patterns of a Rioux Landcut are finite but seem infinite, seem stable but are inherently destabilizing, seem disparate but are, in fact, phenomenally intermeshed. There is a dynamism in this work that engages the eye, the mind—and the solar plexus.

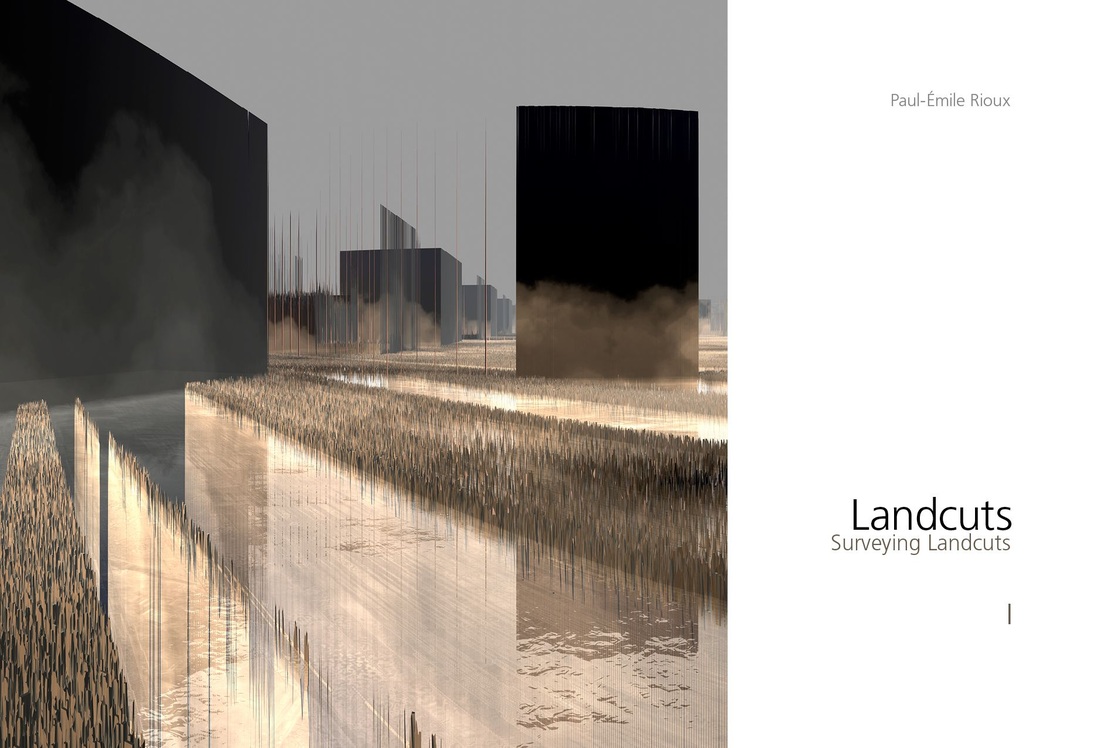

Rioux practices what Ron Hutt has called “Digimorphism,” “an endless loop of sorting, selecting, transforming, and recombining images, marks, colors, forms and texts as they move between digital virtual space and material physical space.” [45] His work is the manifestation of a future that has already arrived and one still accelerating. At the heart of our existential void, Rioux builds stellar digimorphic stuctures that question salient issues of being and dwelling, becoming and inhabitation. His semiotic palimpsests may belong to tomorrow’s dream worlds but they are being bravely built in his studio today. Notes 41.42.44 James Gleick, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood (City: Fourth Estate; First Edition, 2011), page ?. 43. Edward N. Lorenz, The Essence of Chaos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993) 45. Ron Hutt, “Digimorphism,” see online text http://www.ronhutt.org/ |

Rioux practices what Ron Hutt has called “Digimorphism,” “an endless loop of sorting, selecting, transforming, and recombining images, marks, colors, forms and texts as they move between digital virtual space and material physical space.” The richly organized patterns of a Rioux Landcut are finite but seem infinite, seem stable but are inherently destabilizing, seem disparate but are, in fact, phenomenally intermeshed.

|

|

|